Influencers of pre Roman tribes were The Scythians – the Greeks’ name for this initially nomadic people. They inhabited Scythia from at least the 11th century BCE to the 2nd century CE. This included Kazakhstan, thought to be the location for the first area where people domesticated horses, an incredibly important development for the western world. Numerous tribes spread into the vastness of the Eurasian steppes which cover thousands of miles, from Mongolia to Eastern Europe, creating what one researcher calls a “highway” for cultural exchange and conquest.

Whilst the Scythian tribes evolved during the Neolithic, they gained skills in metallurgy. The Chalcolithic (English: /ˌkælkəˈlɪθɪk/; Greek: χαλκός khalkós, “copper” and λίθος líthos, “stone”) period or Copper Age, also known as the Eneolithic or Æneolithic (from Latin aeneus “of copper”), was a period in the development of human technology, before it was discovered that adding tin to copper formed the harder bronze, leading to the Bronze Age. The Copper Age was originally defined as a transition between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age, but is now usually considered as belonging to the Neolithic.

The archaeological site of Belovode on the Rudnik mountain in Serbia contains the world’s oldest securely dated evidence of copper smelting from 5000 BCE. The Scythians absorbed this metallurgy understanding and applied it most effectively over thousands of years.

A farming population (I haplogroup) from the Taurus Mountains arrived at Rudnik and this became the first outpost in Europe in the 6004-5960 B.C. in the pass between the Danube and the Carpathians. Before the arrival of the Romans, the area was inhabited by the Illyrians, followed by the Celts. The Greeks and Romans, keen to name these tribes, provided the classifications we still use today.

The Scythians were highly successful traders over a huge area, a mixture of tribes with variable skills.

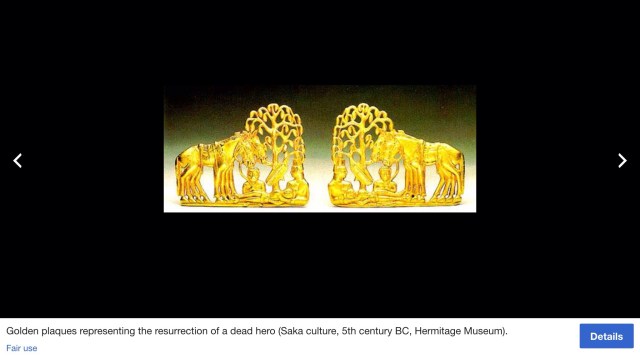

The term Scythic may be used, “to describe a special phase that followed the widespread diffusion of mounted nomadism, characterized by the presence of special weapons, horse gear, and animal art in the form of metal plaques”.

The Scythians worked in a wide variety of materials such as gold, wood, leather, bone, bronze, iron, silver and electrum. Clothes and horse-trappings were sewn with small plaques in metal and other materials, and larger ones, including some of the most famous, probably decorated shields or wagons. Wool felt was used for highly decorated clothes, tents and horse-trappings, and an important nomad mounted on his horse in his best outfit must have presented a very colourful and exotic sight. As nomads, the Scythians produced entirely portable objects; to decorate their horses, clothes, tents and wagons – with the exception in some areas of kurgan stelae, stone stelae carved somewhat crudely to depict a human figure, which were probably intended as memorials. Bronze-casting of very high quality is the main metal technique used across the Eurasian steppe, but the Scythians are distinguished by their frequent use of gold at many sites; although large hoards of gold objects have also been found further east, as in the hoard of over 20,000 pieces of “Bactrian Gold” in partly nomadic styles from Tillya Tepe in Afghanistan.

Image of plaque from Saka (N.B. Saka is an Iranian word equivalent to the Greek Scythes, and many scholars refer to them together as Saka-Scythian), Sakas were Iranian-speaking horse nomads who deployed chariots in battle, sacrificed horses, and buried their dead in barrows or mound tombs called kurgans.

The Scythians did accept defeat at one time, after warring with another tribe for land control. King Darius, king of the Achaemenid Empire, in 513 BC, finally exercised his naval strength in the area they had dominated. The Achaemenid Empire was created by nomadic Persians. The name “Persia” is a Greek and Latin pronunciation of the native word referring to the country of the people originating from Persis (Old Persian: Pārsa), their home territory located north of the Persian Gulf in southwestern Iran.

The Scythians had invaded Media, revolted against Darius and threatened to disrupt trade between Central Asia and the shores of the Black Sea (as they lived between the Danube and Don Rivers and the Black Sea). The campaigns took place in parts of the Balkans and Eastern Europe proper, while principally in what is modern-day Ukraine and southern Russia and they were driven from the Near East. In the first half of the 6th century BCEE, Scythians had to re-conquer lands north of the Black Sea. In the second half of that century, Scythians succeeded in dominating the agricultural tribes of the forest-steppe and placed them under tribute. As a result, their state was reconstructed with the appearance of the Second Scythian Kingdom which reached its zenith in the 4th century BCE.

Map revealing the distances the mobile Scythians were willing to travel to expand their territory. In the case of Media, for example.

Today, a project led by Danish evolutionary geneticist Eske Willerslev has collected a massive amount of genetic data across the steppes. Genetically speaking, based on this research, it appears that earlier Western Eurasian farmers, already living on the steppes 5,000 years ago, were gradually replaced by mounted warriors of East Asian descent in several waves of migration that continued well into historic times.

This genomic research is beginning to challenge some of David Anthony’s work (see details below). For example, the team uncovered suggestions of two waves of migration into South Asia: a very early one prior to the Bronze Age (ruling out the Early Bronze Age Yamnaya and Afanasievo) and a second during the Late Bronze Age, 3,200-4,300 years ago, which may have introduced Indo-Iranian languages into the region.

The area of the East Mediterranean in 6000 B.C., influenced by the Scythian horsemanship and military acumen, led to the Mycenaean Minoan cultures which in turn became the forcing ground for the great civilisations of Greece and Rome.

Without the domestication of horses by, most probably, the people of Kazakhstan’s Akmola Province, and the invention of the wheel, imported from the civilized Middle East, which had arrived in the steppe around 3100 BCE, we would not have seen the invention of the chariot in the steppe. It may be the chariot was originally meant as an improved tool for hunting – used roughly by 2000 BCE, probably in the area just east of the southern Ural mountains, where the oldest chariots have been unearthed.

Despite new genetic information, we can refer, in the meantime, to the still convincing body of work by David Anthony, but remember it is healthy to remain curious and sceptical as new sciences discover more fascinating insights.

The title of David Anthony’s book says it all really.

Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse The Wheel And Language. How Bronze-Age Riders From the Eurasian Steppes Shaped The Modern World. Princeton University Press.

According to Anthony, between 3100–3000 BC, a massive migration of Indo-Europeans from the Yamna culture took place into the Danube Valley. This link to the Yamna is now disputed, but the Yamna are of great interest nonetheless.

Map showing Danube valley

The Yamna culture originated in the Don–Volga area,

Map of Don-Volga area

and is dated 3300–2600 BC. It was preceded by the middle Volga-based Khvalynsk culture and the Don-based Repin culture (ca. 3950–3300 BC), and late pottery from these two cultures can barely be distinguished from early Yamna pottery.

According to Anthony (2007), the early Yamnaya horizon spread quickly across the Pontic–Caspian steppes between ca. 4000 and 3200 BC.

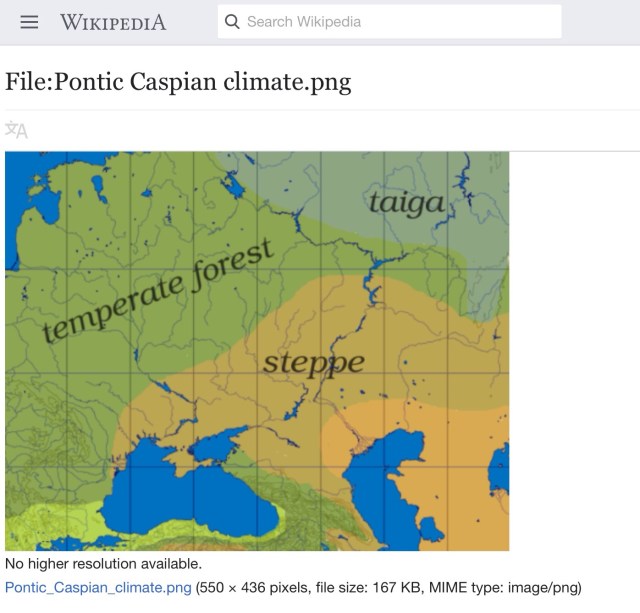

Image of map of Pontic-Caspian steppes

The Pontic–Caspian steppe, Pontic steppe or Ukrainian steppe is the vast steppeland stretching from the northern shores of the Black Sea (called Euxeinos Pontos [Εὔξεινος Πόντος] in antiquity) as far east as the Caspian Sea, from Moldova and eastern Ukraine across the Southern Federal District and the Volga Federal District of Russia to western Kazakhstan, forming part of the larger Eurasian steppe, adjacent to the Kazakh steppe to the east. It is a part of the Palearctic temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands ecoregion of the temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands biome.

The area corresponds to Cimmeria, Scythia, and Sarmatia of classical antiquity. Across several millennia the steppe was used by numerous tribes of nomadic horsemen, many of which went on to conquer lands in the settled regions of Europe and in western and southern Asia.

The term ‘Ponto-Caspian region’ is used in biogeography for plants and animals of these steppes, and animals from the Black, Caspian, and Azov seas. Genetic research has identified this region as the most probable place where horses were first domesticated.

According to the dominant Kurgan hypothesis in Indo-European studies, the Pontic–Caspian steppe was the homeland of the speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language, and these same speakers were the original domesticators of the horse.

Kazakhstan’s Akmola Province is believed to be the location of the earliest domestication efforts, while other discoveries place this activity as far back as 4000-3500 years BC, in the Eurasian Steppes.

Image of horses

According to Anthony, “the spread of the Yamnaya horizon was the material expression of the spread of late Proto-Indo-European across the Pontic–Caspian steppes.” Anthony further notes that “the Yamnaya horizon is the visible archaeological expression of a social adjustment to high mobility – the invention of the political infrastructure to manage larger herds from mobile homes based in the steppes.”

According to Pavel Dolukhanov the emergence of the Pit-Grave culture represents a social development of various local Bronze Age cultures, representing “an expression of social stratification and the emergence of chiefdom-type nomadic social structures”, which in turn intensified inter-group contacts between essentially heterogeneous social groups.

The genetic basis of a number of physical features of the Yamnaya people were ascertained by the ancient DNA study conducted by Haak et al. (2015), Wilde et al. (2014), Mathieson et al. (2015): they were genetically tall (phenotypic height is determined by both genetics and environmental factors), overwhelmingly dark-eyed (brown), dark-haired and had a skin colour that was moderately light, though somewhat darker than that of the average modern European.

Their dialects might then have developed into Proto-Celtic. The arrival of Indo-Europeans into Italy is in some sources ascribed to the Beakers. A migration across the Alps from East-Central Europe by Italic tribes is though to have occurred around 1800 BC.

From the late 3rd to the early 2nd millennium BC, tribes coming both from the north and from Franco-Iberia brought the Beaker culture and the use of bronze smithing, to the Po Valley, to Tuscany and to the coasts of Sardinia and Sicily.

The Bell Beaker culture is understood as not only a particular pottery type, but also a complete and complex cultural phenomenon involving metalwork in copper and gold, archery, specific types of ornamentation and shared ideological, cultural and religious ideas. The Bell Beaker period marks a period of cultural contact in Atlantic and Western Europe on a scale not seen previously, nor seen again in succeeding periods.

The Beakers could have been the link which brought the Yamna dialects from Hungary to Austria and Bavaria.

When the massive migration (thought to be militaristic in nature) moved over the land, their people, often warriors, died along the way, and the tradition was to build a kurgan – and these have been found by archaeologists:

Image of kurgan

The Kurgan people culture existed during the fifth, fourth, and third millennia BC; they lived in northern Europe, from N.Pontic across Central Europe. The word “kurgan” means a mound or a barrow in Türkic. Kurgan culture is characterized by pit-graves or barrows, a particular method of burial. They are also called the Pit-grave people (Pit-grave culture), or Barrow people (Barrow culture).

Thousands of kurgans are attributed to this event. These migrations probably split off Pre-Italic, Pre-Celtic and Pre-Germanic from Proto-Indo-European. By this time the Anatolian peoples and the Tocharians had already split off from other Indo-Europeans.

During the late Bronze Age, the Urnfield culture (cremation of their dead and ashes placed in special urns) might have brought proto-Italic people from among the “Italo-Celtic” tribes who remained in Hungary into Italy. These tribes are thought to have penetrated Italy from the east during the late 2nd millennium BC through the Proto-Villanovan culture. They later crossed the Apennine Mountains and settled central Italy, including Latium.

In the mid-2nd millennium BC, the Terramare culture developed in the Po Valley. The Terramare culture takes its name from the black earth (terra marna) residue of settlement mounds, which have long served the fertilizing needs of local farmers. These people were still hunters, but had domesticated animals; they were fairly skillful metallurgists, casting bronze in moulds of stone and clay, and they were also agriculturists, cultivating beans, the vine, wheat and flax. The Latino-Faliscan people have been associated with this culture, especially by the archaeologist Luigi Pigorini.

During the Late Bronze Age (1350-1150 BC), we can hypothesise a greater degree of diversified territorial organisation, including centres which are larger and tending towards hegemony, adjacent to smaller sites. In certain areas during the Late Bronze Age (LBA) we see a higher frequency of sites occupying a larger extension and a scant presence of small-size settlements, perhaps due to a marked tendency towards concentration of population. This trend seems to be accentuated during the advanced LBA, when the overall number of settlements decreases, with a tendency towards concentration in larger-size settlements and probable subordination of the smaller settlements to the larger ones.

Scientists examined 7,000-year-old ancient pollen and charcoal samples from the Nile to piece together the time – and found evidence of a ‘mega drought’ in the the area.

The droughts brought fires, famine and social unrest to the region. Pollen grains obtained from the bottom of the Sea of Galilee have also provided similar evidence that the region endured a 150 year drought between 1250BC and 1100BC.

Professor Eric Cline, director of the Capitol Archaeological Institute at George Washington University says there was a sharp decline around 1250 BCE in oaks, pines, and carob trees—the traditional flora of the Mediterranean in the Late Bronze Age.

Plants usually found in semiarid desert regions increased while the number of olive trees – an important crop plant – also declined.

And so we find that, around 1200 BC, a serious crisis began for the terramare culture that within a few years led to the abandonment of all the settlements; the reasons for this crisis, roughly contemporaneous with the LBA collapse in the eastern Mediterranean, are still not entirely clear. It seems possible that, in the face of an incipient overpopulation (between 150,000 and 200,000 individuals were calculated) and depletion of natural resources, a series of drought periods led to a deep economic crisis, famine, and consequently the disruption of the political order, which caused the collapse of society. Around 1150 B.C. the terramare were completely abandoned, with no settlements replacing them. The plains, especially in the area of Emilia, were abandoned for several centuries, and only in the Roman era did they regain the density of population reached during the terramare period.

Finally, we gradually see the tribes of central Italy going through evolved stages toward the formation of a pre-Roman existence. Rome was to be eventually located some distance from the earthquake prone Apennines.

Archaeologists divide the pre-Roman history of central Italy into three periods:

1. Proto-Villanovan (1200 BC – 1000 BC)

The Proto-Villanovan culture dominated the peninsula and replaced the preceding Apennine culture. The Proto-Villanovans practiced cremation and buried the ashes of their dead in pottery urns of a distinctive double-cone shape. Generally speaking, Proto-Villanovan settlements have been found in almost the whole Italian peninsula from Veneto to eastern Sicily, although they were most numerous in the northern-central part of Italy. The most important settlements excavated are those of Frattesina in Veneto region, Bismantova in Emilia-Romagna and near the Monti della Tolfa, north of Rome. The Osco-Umbrians, the Veneti, and possibly the Latino-Faliscans too, have been associated with this culture.

2. Villanovan (1000 BC – 750 BC)

The Villanovan culture is closely associated with the Celtic Halstatt culture of Alpine Austria, and is characterised by the introduction of iron-working, the practice of cremation coupled with the burial of the ashes in distinctive pottery. The earliest remains of Villanovan culture date back to approx. 1100 BC

3. Etruscan (750 BC – 300 BC)

The Etruscans, to the north, provided a model for trade and urban luxury. Etruria was also well situated for trade and the early Romans either learned the skills of trade from Etruscan example or were taught directly by the Etruscans who made incursions into the area around Rome sometime between 650 and 600 BCE (although their influence was felt much earlier). The extent of the role the Etruscans played in the development of Roman culture and society is debated, but there seems little doubt they had a significant impact at an early stage.

At one time researchers thought these were three separate cultures. Today, they tend to consider them three phases of a single, evolving culture.

And last, but not least, bear in mind the seismic activity of the Apennine Mountains, a significant feature of Italy.

Map of Italy highlighting the Apennine range

The Abruzzi Apennines, located in Abruzzo, Molise (formerly part of Abruzzo) and southeastern Lazio, contain the highest peaks and most rugged terrain of the Apennines. They are known in history as the territory of the Italic peoples first defeated by the city of Rome.

The Apennines also conserve some intact ecosystems, which have survived human intervention. In here there are some of the best preserved forests and montane grasslands in the whole continent; now protected by national parks and, within them, a high diversity of flora and fauna. These mountains are, in fact, one of the last refuges for the big European predators such as the Italian wolf and the marsican brown bear, now extinct in other countries of central Europe.

The mountains lend their name to the Apennine peninsula, which forms the major part of Italy. They are mostly verdant, although one side of the highest peak, Corno Grande is partially covered by Calderone glacier, the only glacier in the Apennines. It has been receding since 1794. The eastern slopes down to the Adriatic Sea are steep, while the western slopes form foothills on which most of peninsular Italy’s cities are located. The mountains tend to be named from the province or provinces in which they are located; for example, the Ligurian Apennines are in Liguria. As the provincial borders have not always been stable, this practice has resulted in some confusion about exactly where the montane borders are. Often but not always a geographical feature can be found that lends itself to being a border.

60 kilometer to the East of present day Rome runs the Apennine mountain chain, and here there are earthquakes. It is the distant echoes of these quakes which so damaged the Colosseum.

And the scene is set for my next blog, the tribes who built the Mesoamerican city of Teohuacan compared with the tribes who went on to build the city of Rome.

You must be logged in to post a comment.